Spotlights of the SOEP-CoV Study (1)

Version: 26 Juni 2020

Family Life During Corona

von Sabine Zinn

The restrictions to contain the coronavirus have had sweeping effects on family life in Germany so far, and continue to have an impact. Schools throughout the country are slowly beginning to reopen, while childcare is still only available for specific groups children (pre-school children, children of single parents, and children of essential workers in particular). Meanwhile, many parents are still working partially or completely from home.

How are parents managing childcare and housework?

In this report, we look at how families are dealing with the coronavirus restrictions. How are parents handling childcare alongside normal household responsibilities (cooking, cleaning, laundry)? Are there differences between women and men, and between families in East and West Germany? How does parents’ employment status affect these differences?

To answer these questions, we used SOEP-CoV data on the amount of time spent on childcare and housework in April 2020 in households with children up to 16 years of age. To study how the amount of time women and men spend on these tasks has changed, we used comparable Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP) data from 2019. The SOEP data allow us to project results to the total population of private households in Germany for every year from 1984 to the present.

The results of our analysis show that during the corona pandemic, both women and men were spending on average more time per weekday on childcare and housework than in 2019, but that women were still spending more time than men on both childcare and housework. In April 2020, women spent 7.6 hours and men 4.2 hours per weekday on childcare, and both women and men spent about a half hour more on housework than they had in the previous year. In 2019, women spent an average of 2.1 hours and men just under 1 hour per weekday on housework, and women spent an average of 5.3 hours and men 2 hours per weekday on childcare.

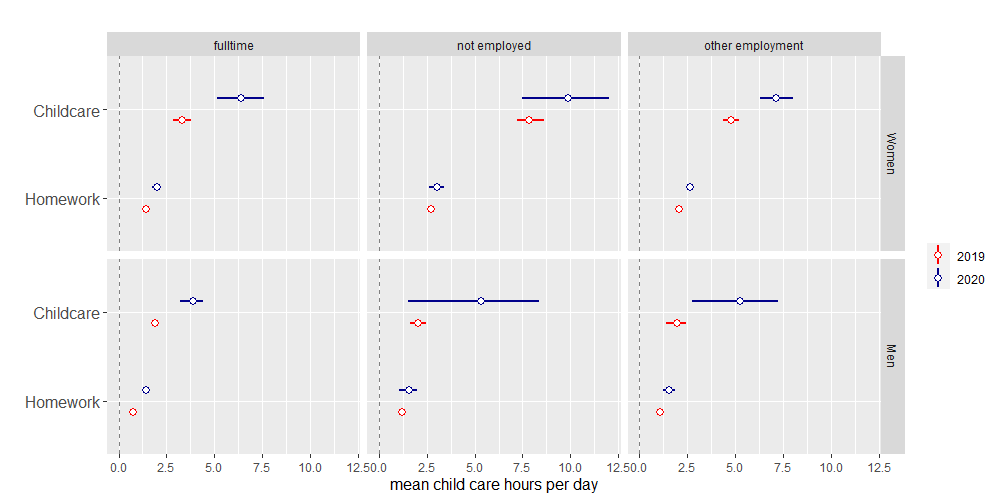

The figure below shows the average number of hours that women and men with children up to 16 years of age spent per weekday on childcare and housework in April 2020 during the corona pandemic. The graph differentiates by employment status among individuals working full-time at the time of the survey, those not in employment, and those in other forms of employment (such as part-time work, “short-time work”, apprenticeship or training). The horizontal lines on each mean value represent the 95% confidence intervals (and thus the uncertainty in the estimates generated by the sampling procedure).

For childcare, the results show that, as expected, people in all employment status groups were spending more time during the week on childcare in April 2020 than in the previous year. The increase in time spent on childcare was 3 hours for women working full-time, about 2 hours for non-employed women, and about 2.3 hours for women in other forms of employment. For men, the increase was around 2 hours on average for men working full-time, and 3.3 hours on average for all other men.

For housework, the results show that women in full-time employment and women in other forms of employment (such as part-time) spent about half an hour per day more in April 2020 than in the previous year, while non-employed women spent the same number of hours as in 2019. Men spent an average of 30 minutes more on housework in 2020 no matter what their employment status.

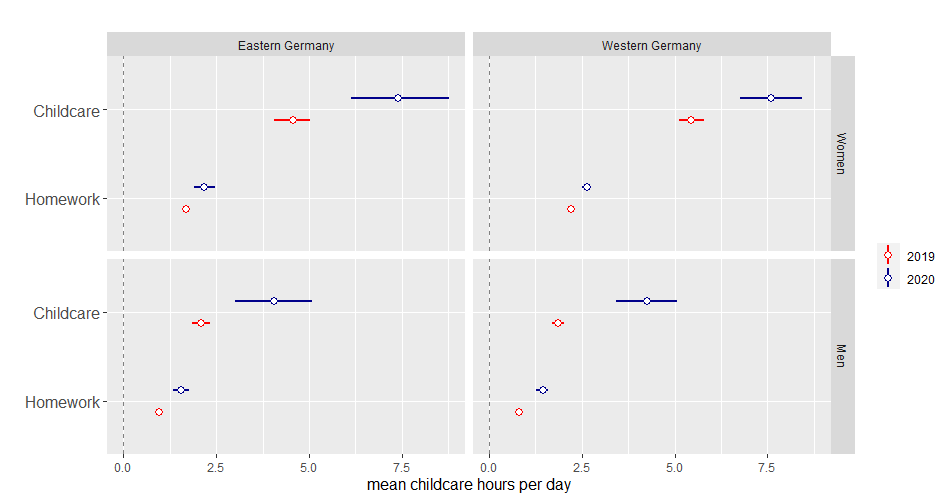

The results show no differences between East and West Germany in the number of hours men and women spent on housework and childcare in 2019 and 2020, as seen in the second figure below.

Takeaway No. 1:

Both men and women in households with children up to 16 years of age spent more time on childcare and housework on average in April 2020 than in 2019. The increase differs only marginally between women and men. This suggests that the added burden of childcare and housework is being distributed relatively equally between men and women.

It remains to be seen whether the patterns of behavior that have emerged over recent weeks as a result of the coronavirus regulations will continue in families after the lockdowns, school closures, and other measures have come to an end. A positive result is that, as of April 2020, both women and men were sharing the additional work resulting from the lockdown relatively equally in both East and West Germany. The fact that working for home was an option for many employed people may have played a role in this. Another possible factor is the increased flexibility in working hours (available not only to mothers but also to fathers).

Note 1: (i) In this analysis, we do not differentiate by age of the child(ren) and therefore cannot make any statements about how much time mothers and fathers spent caring for children of what age. (ii) The same is true for the number of children: We are unable to say how much time was spent per child. (iii) For 2019, we had data on a total of 7,742 individuals in households with children up to 16 years of age (3,360 men and 4,382 women). In April 2020, during the corona pandemic, we had data on 1,543 individuals (516 men and 1,027 women). All data were weighted to correct for selectivity due to unit nonresponse and adjusted to the distributions in the currently available Microcensus data by household size, household type, federal state, municipality size class, citizenship, gender, and age. (iv) An analysis of the data by educational attainment did not yield significantly different findings than the analysis by employment status. (v) The findings presented here do not confirm the concerns expressed in the DIW Wochenbericht “Corona crisis makes work-life balance more difficult, especially for mothers—the burden should be lightened for working parents” that existing differences between mothers and fathers in the amount of time spent on childcare and housework will continue to increase significantly during the corona pandemic (https://www.diw.de/de/diw_01.c.787888.de/publikationen/wochenberichte/2020_19_1/corona-krise_erschwert_vereinbarkeit_von_beruf_und_familie_v___r_muetter_____ erwerbstaetige_eltern_sollten_entlastet_entlastet_werden.html?pic=figure3#figure3).

How satisfied are parents with schools’ crisis management?

School closures have posed new challenges for both educational authorities as well as teachers and parents. Although it was already apparent in early March 2020 that schools would be forced to close, all those involved were still relatively unprepared when the measures went into effect. It was completely unclear how long schools would remain closed and whether and how teaching would continue.

Experts soon spoke out to say that children would need to continue learning in order to prevent a complete disruption of their education (see, for instance, https://www.ifo.de/en/node/53796). But Germany had no concept for how this could be done, much less an appropriate or tested platform that schools could use for this purpose, either nationwide or at the state level. Schools were therefore forced to adapt to the situation individually and find their own ways of contacting students and providing them with learning materials. This led to the use of a wide variety of strategies in different schools.

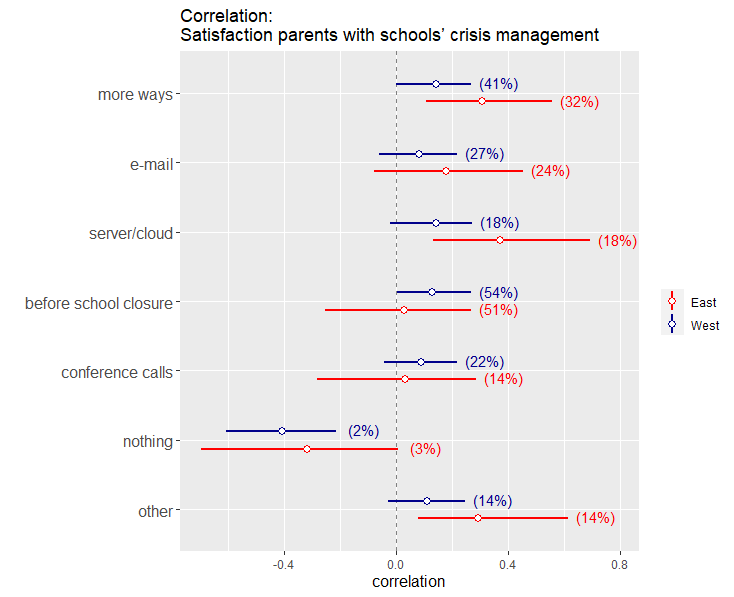

In our study, we asked parents how schools had provided learning materials to their youngest school-aged children. In April 2020, a total of 26% of all parents reported that they had received learning materials by e-mail. The difference between East and West Germany was small: 24% of parents in the East and 27% in the West received materials by e-mail. Eighteen percent of parents reported that learning materials were provided on a server or in the cloud. Fifty-one percent of parents in East Germany and 54% in West Germany received learning materials before schools closed. Fourteen percent of parents in East Germany and 22% in West Germany reported that schools offered conference calls between teachers and students. As many as 2% of all schools provided students with no learning materials of any kind. Fourteen percent of schools provided students with learning materials by other means (for instance, by having students come to school or another location to pick up materials). Parents’ satisfaction with schools’ crisis management may be assumed to depend on how the schools provided their children with learning materials. The figure below shows the correlation (white dots) on a scale from -1 to 1, and the percentage of the means of providing learning materials offered to parents (in parentheses). The horizontal lines indicate the 95% confidence interval for each correlation value (and thus the uncertainty in the estimates generated by the sampling).

Overall, parents’ satisfaction depends only partly on the means by which learning materials were provided. We find no significant correlation, for instance, with e-mail or conference calls. We find positive correlations in East Germany with the use of a server or the cloud, and in West Germany with the provision of learning materials prior to school closure. In East Germany, other methods of getting learning materials to students (such as having students pick them up personally from the teacher or school) led to greater satisfaction with schools’ crisis management. Parents who did not receive learning materials from the school at all were much more dissatisfied. In other words, parents’ satisfaction with schools’ crisis management was within a positive range if the schools reacted in at least some way. In total, 39% of parents received learning materials for their children in more than one of the ways mentioned. Parents in both East and West Germany saw this as positive. The differences between East and West Germany for parents’ overall satisfaction with schools’ crisis management were low. Differences between parents in East and West were also low for the means schools used to provide the materials.

Takeaway No. 2:

In summary, the results show that as of April 2020, schools had provided most parents with learning materials for their youngest school-aged child. This shows that even without the existence of a nationwide concept or platform, most schools had succeeded in making direct contact with parents. This indicates great flexibility on the part of schools, administrators, and teachers and their ability to improvise and to react effectively, even in an exceptional situation. Nevertheless, the low proportion of digital solutions is surprising: just 18 percent of parents had been provided with learning materials on a server or in the cloud. In East Germany, only 13 percent of parents had been offered conference calls for their youngest school-aged child; in West Germany, the figure was 22 percent. These percentages must be regarded as relatively low in the age of digitization. It is clearly time for schools across Germany to modernize in this respect.

Note 2: (i) In this study, no distinction was made between school types, since this information is not available for the SOEP-CoV study. (ii) Similarly, all school-aged children were considered together. Thus, no conclusions can be drawn from the results regarding the appropriateness of the measures to the age and/or grade of the children. (iii) We used data from 1,311 parents (from different households) with school-aged children. All data were weighted to correct for selectivity due to unit nonresponse and adjusted to the distributions in the currently available Microcensus data by household size, household type, federal state, municipality size class, nationality, gender, and age. (iv) Statements on the quality of the materials provided are not possible with the SOEP-CoV data.

I am grateful to Michaela Kreyenfeld for her valuable assistance in analyzing the SOEP-CoV data on childcare and housework.